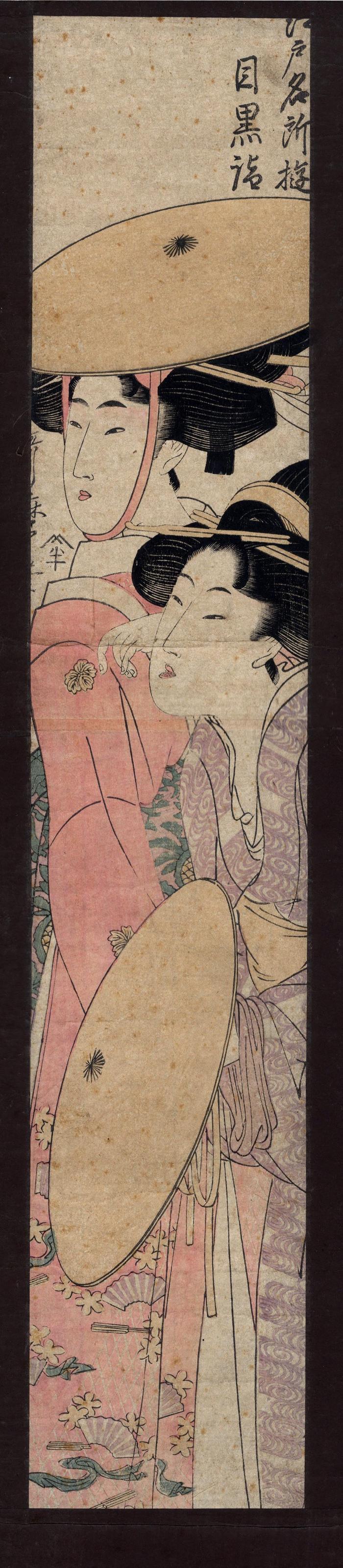

Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川歌麿) (artist ca 1753 – 1806)

Visit to Meguro or Meguro mairi (目黒詣) from the series Edo Meisho asobi (江戸名所遊)

ca 1800

4.3 in x 23.3 in (Overall dimensions) color woodblock print

Signed: Utamaro hitsu (哥麿筆)

Publisher: Surugaya Hanbei (Marks 499 - seal 02-062)

British Museum - said to be by Utamaro I from the 1790s

Google maps - Meguro Ward, Tokyo - highlighted in red

Lyon Collection - Eisui pillar print of the lovers Komurasaki and Gonpachi

Dayton Art Institute

National Gallery, Prague

Princeton University Art Museum

New York Public Library - said to be by Utamaro II and dated to 1807

Why Meguro?

Why did people make the pilgrimage to Meguro, a place some miles to the southeast of Edo? We don't know for sure, but Paul Waley in Tokyo: City of Stories may have provided one of the reasons on pp. 236-37.

"At the beginning of the seventeenth century, soon after Tokugawa had made Edo their capital, one of Ieyasu's closest advisers, the abbot Tenkai, decided that the new city needed greater protection than the castle could ever afford it. He decreed that five temples should be established on the outskirts of the city, each temple to house an image of Fudō with different-colored eyes, each image representing one of the five elements. The temples became popular places of pilgrimage and recreation in the Edo period, in particular the Black-Eyed (Meguro) Fudō, which once stood some way outside the city limits. A.B. Mitford records his impressions of Meguro as it was in the Edo period. 'As we draw near to Meguro, the scenery, becoming more and more rustic, increases in beauty... Close at our feet runs a stream of pure water, in which a group of countrymen are washing the vegetables which they will presently shoulder and carry off to sell by auction in the suburbs of Yedo.'

At length, Mitford reaches the village of Meguro, at the gates of the temple to the Black-Eyed Fudō. 'Meguro is one of the many places round Yedo to which the good citizens flock for purposes convivial or religious, or both, hence it is that, cheek by jowl with the old shrines and temples, you will find many a pretty tea-house.' The 'purposes religious' that Mitford refers to were not the normal perfunctory prayer at a temple or shrine. In the grounds of the Meguro Fudō was a pond, the pond of purification, into which water gushed (as it does to this day) from the pouting mouths of two bronze dragons. Penitents, ascetics, and all manner of pious folk would come to the temple and stand under the water in order to purify the soul as the body was cleansed, the colder the day the more efficacious the cleansing."

But there is a more probable reason why these two lovelies went to Meguro

There is another pillar print by Eisui in the Lyon Collection showing the two lovers Gonpachi and Komurasaki. He was handsome and dashing in the later theatrical production based on the tragedy of their affair, but what he was in real life, or the character he was built on, was a murderer and general criminal who was captured, tried and executed for his crimes. As the story was later romanticized Komurasaki committed suicide at his grave.

David Waterhouse in his brilliant work on the collection of Harunobu prints in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston wrote: "In later years the place became a shrine to the two, and it was traditionally put at Tōshōji, a small monastery adjacent to the Meguro Fudō.... The memorial to Komurasaki and Gonpachi came to be known as hiyoku-zuka, 'lovers' mound'..." This might well be the motive for these two women who were making their pilgrimage to Meguro. Waterhouse later noted that the memorial was moved several times over the years. As of 1955 it could be found in the garden of a local restaurant.

****

In One Hundred Views of Edo: Woodblock Prints by Ando Hiroshige Mikhail Uspensky shows us three different prints devoted to the Meguro area: 1) The Chiyogaike Pond at Meguro; 2) New Fuji at Meguro; and 3) The Original Fuji at Meguro.

On page 64 Ouspensky reiterates the story of the founding of Fudō temples and stresses the significance of the one at Meguro because it was the largest of them and thus the most important "...although there are no notable sights here. Even the waterfall which dropped in stages into the Chiyogaike pond (it existed until the 1930s) was never particularly famous, nor was the pond itself, named after a certain drowned O-Chiyo, the wife of a samurai who drowned herself in it after her husband died in battle."

Uspensky notes that: "In Hiroshige's time, Meguro was part of the quiet outskirts of forests and fields [of Edo]. From time to time the shoguns practised falconry here, while in spring the peasants gathered young bamboo shoots which they sold by the gate of the Ryusenji monastery."

In the section on the New Fuji at Meguro notes that this miniaturized hill done in the shape of Japan's most identifiable symbol was not built until 1829, almost thirty years after this Utamaro prints was published.

****

A Postscript

When we started looking into the the subject of Meguro we found a larger visual library than a written one. It turns out that quite a few artists other than Utamaro chose something in the Meguro area as a focal point for one or more of their prints. Most of the images are landscapes, but not all of them. Harunobu created Autumn Flowers in Meguro, featuring a young woman and her even younger attendant, with little emphasis on anything floral. Hiroshige did quite a few prints related to Meguro and Hokusai did several. Toyokuni I showed one of the temples, while his pupil Kunisada featured a server in a restaurant with a smaller inset in the upper right of the Fudō temple. Gakutei featured a shop girl in a beautiful surimono. Even Hasui, in 1931, created a gorgeous, sun-dappled image of a woman entering the temple. Clearly Meguro was a destination of some relative importance - if only for something to do outside of the urban sprawl of Edo on a pleasant day.

****

Illustrated in black and white in The Japanese Pillar Print by Jacob Pins, Robert G. Sawers Publishing, 1982, page 280, #769 .

pillar print (hashira-e - 柱絵) (genre)

Surugaya Hanbei (駿河屋半兵衛) (publisher)

beautiful woman picture (bijin-ga - 美人画) (genre)