Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川国芳) (artist 11/15/1797 – 03/05/1861)

Kuwana Station: Story of Sailor Tokuzō (Kuwana - 桑名: Funanori Tokuzō no den - 船のり徳蔵の傳) from the series 53 Stations of the Eastern Sea Road (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui - 東海道五十三対)

National Museum of Asian Art There are nine prints from this series, Fifty-three Pairings for the Tōkaidō Road (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui - 東海道五十三対), in the Lyon Collection. See also #s 382, 815, 816, 819, 861, 1022, 1095 and 1269.

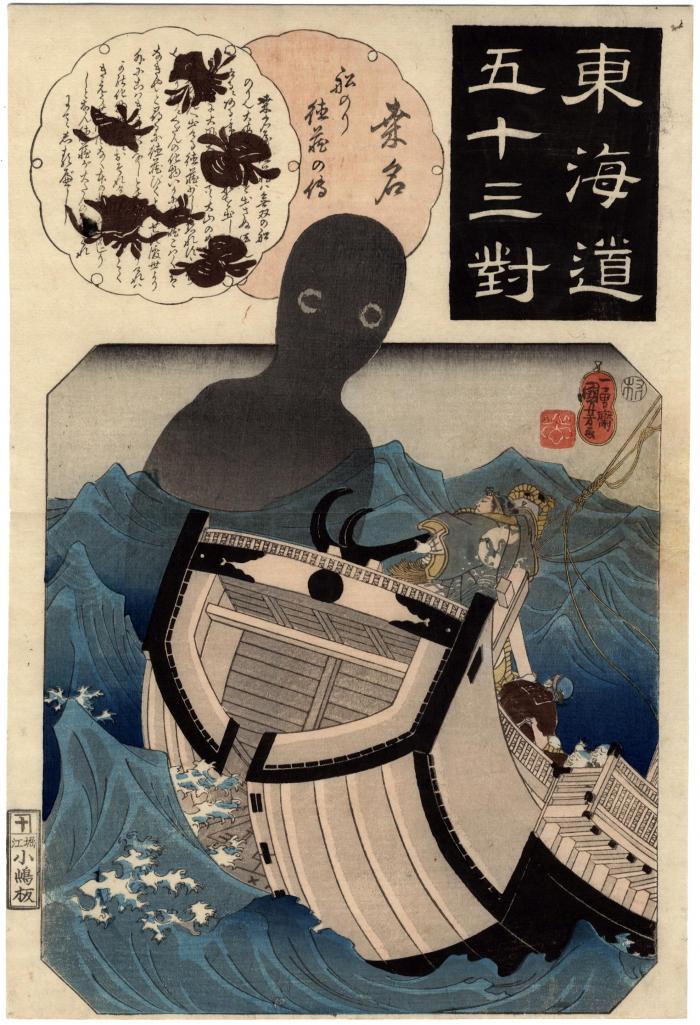

Station #43, from a series collaborated by artists Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III). Image depicts apparition of the "sea monk," umibōzu, towering over the ship captain Tokuzō.

An umibōzu, sea monster, appears frequently in coastal folklore and Edo period writings. It is notorious for wrecking boats and dragging people into the sea. A well-known umibōzu tale appears in the Usō Kanwa 雨窓閑話, a collection of stories from the late Edo period:

A noted sailor by the name of Kuwana no Tokuzō 桑名の徳蔵 violates the taboo on boating at the end of the month and goes out to sea alone. Sure enough, he encounters a great nyūdō (a euphemism for a bald-headed monster) 1 jō (~3 meters or 10 feet) in height, with terrible eyes like scarlet mirrors. The ōnyūdō asks Tokuzō if he finds its shape frightening, but the sailor replies that he finds nothing frightening but making his way in the world. With no reply to this wit, the umibōzu vanishes instantly.

****

The curatorial files from the Walters Museum of Art say:

The Sea Monk (Umi Bozu) is a sea monster with a smooth round head, like the shaven head of a Buddhist monk. This woodblock print illustrates the story of the sailor Kawanaya Tokuzo, who decides to go to sea on the last day of the year, which other sailors consider unlucky. A violent storm breaks out, and the Umi Bozu appears. In a ghastly voice the apparition demands, "Name the most horrible thing you know!" Tokuzo yells back, "My profession is the most horrible thing I know!" The monster is apparently satisfied with this answer and disappears along with the storm.****

The text at the top in the snowflake, fan-shaped cartouches reads: 船のり徳蔵の傳

桑名屋徳蔵は無双の船のり也 大晦日には船を出さぬ法也けるに ある年大晦日に船を出し 沖中にて俄に大風大波立て 大山の如き大坊主船の先へ出ける 徳蔵少しも恐れずかぢを取り行に くだんの化物 いかに徳蔵こわくはなきや と尋るに 徳蔵びくともせず 渡世より外にこはきものはなし と大おんによばわりたれば かの化物此一言におそれけん 雪霜のごとくきえうせ 波風なく本の如くに船ははしりしとなん 徳蔵が大たんのほどこれにてしるべし

The translation reads: "The Legend of the Sailor Tokuzō

Kuwanaya Tokuzō was the toughest sailor. Although there was a law that prohibited sailing on New Year's Eve, he disregarded it and sailed offshore on that day. Suddenly the wind picked up and the sea became rough. A huge monster called Ōbōzu emerged, looming like a mountain ahead of the boat. However, Tokuzō showed no fear and steered his boat as if nothing was happening. Then the monster asked Tokuzō why he was not scared. Tokuzō shouted that he feared only for his livelihood. The monster was surprised and frightened of Tokuzō, and immediately disappeared. Now the ocean became calm, and Tokuzō smoothly steered for the coast. This story tells you how fearless and courageous Tokuzō was."

Quoted from: Tōkaidō Texts and Tales: Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui by Kuniyoshi, Hiroshige, and Kunisada, edited by Andreas Marks, p. 131.

The explanatory notes add: "The legend was first dramatized in The Tale of Kuwanaya Tokuzō's Boat Entering the Port (Kuwanaya Tokuzō irifune monogatari), staged at Osaka's Ogawa Theater in the twelfth month of 1770. The story takes place on the Enshū Sea off Shizuoka, but because of the pun on the Tōkaidō station Kuwana, Tokuzō is connected to this station." (Ibid.)

****

Lafcadio Hearn in his Romance of the Milky Way and other studies and stories wrote of the umi-bōzu in his 1910 edition on pages 123=124: "Place a large cuttlefish on a table, body upwards and tentacles downwards - and you will have before you the grotesque reality that first suggested the fancy of the Umi-bōzu, or Priest of the Sea. For the great bald body in this position, with the staring eyes below, bears a distorted resemblance to the shaven head of a priest; while the crawling tentacles underneath (which in some species are united by a dark web) suggest the wavering motions of the priest's upper robe.... The Umi-bōzu figures a good deal in the literature of Japanese goblinry, and in the old fashioned picture-books. He rises from the deep in foul weather to seize his prey."

Hearn then gives quotes a poem which treats with this subject:

Shita wa Jigoku ni,

Sumizomé no

Bōzu no umi ni

Déru mo ayashina!

(Since there is the thickness of but a single

plank [between the voyager and the sea], and un-

derneath is Hell, 'tis indeed a weird thing that

a black-robed priest should rise from the sea [or,

"tis surely a marvelous happening that," etc!]

****

Illustrated in:

1) color in Kunisada's Tōkaidō: Riddles in Japanese Woodblock Prints by Andreas Marks, Hotei Publishing, 2013, page 106, #T78-43.

2) a small black and white reproduction in Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide by Hiroko Yoko and Matt Alt, Kodansha International, 2008, page 52.

3) color, six different times, in Tōkaidō Texts and Tales: Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui by Kuniyoshi, Hiroshige, and Kunisada, edited by Andreas Marks with contributions by Laura W. Allen and Ann Wehmeyer, University Press of Florida, 2015, on pages 2, 31, 132 (two versions) and 181 (two versions).

Laura Allen notes on page 3 the origin of the name Kuwanaya Tokuzō: "A fictional character, Tokuzō was introduced to the public in the kabuki play The Tale of Kuwanaya Tokuzō's Boat Entering the Port (Kuwanaya Tokuzō irifune monogatari), which was premiered in Osaka in 1770. Seeking novelty within the known conventions of Tōkaidō imagery, Kuniyoshi cleverly substitutes a storm-tossed boat for Kuwana's typical sleepy coastal landscape."

4) color in an online publication, 'Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui – Uma Série Japonesa na Coleção do Museu Calouste Gulbenkian' by Beatriz Quintais Dantas, her master's thesis, Anexo 51, p. 24, April, 2021. The author used the same as the example in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. There is also a small color reproduction of the copy found in the Gulbenkian Collection at #43.

5) a full page black and white reproduction in Kuniyoshi by B. W. Robinson, London, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1961, #49. Robinson titled this as "Apparition of the "Sea Monk"."

6) black and white in the Catalogue of the Van Gogh Museum's Collection of Japanese Prints by Charlotte van Rappard-Boon, Willem van Gulik and Keiko van Bremen-Ito, 1991, p. 288, #421.

7) black and white in 'A Remarkable Tōkaidō Set (2)' by Helmut Wilmes in Andon 60, September, 1998, fig. 4, p. 37.

8) color in Japanese Yōkai and Other Supernatural Beings: Authentic Paintings and Prints of 100 Ghosts, Demons, Monsters and Magicians by Andreas Marks, Tuttle Publishing, 2023, p. 120. This exact print is the one illustrated in this volume.

9) in color in Utagawa Kuniyoshi: 342 Color Paintings [sic] of Utagawa Kuniyoshi by Jacek Michalak, Kindle Edition, 2022, unpaginated.

****

The original Tōkaidō was established by the Kamakura bakufu (1192-1333) to run from Kamakura to the imperial capital of Kyoto.

****

The Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui: A collaborative work

Andreas Marks wrote in 'When two Utagawa masters get together. The artistic relationship between Hiroshige and Kunisada' in Andon 84, November 2008, pp. 37 and 39:

"The artistic relationship between Hiroshige and Kunisada entered a new period in 1845, when both artists were commissioned to contribute to the series Fifty-Three Pairs of the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui). The Fifty-Three Pairs of the Tōkaidō is an example of a series where a number of artists were commissioned to contribute complete and individual designs under a specific theme. A few years before, the Kisokaidō series by Hiroshige and Eisen had been published with the same concept. This concept became quite common in the second half of the 1840s until the early 1850s, and sometimes the artists were supported by their disciples who drew inset cartouches.

The main contributor to the Fifty-three Pairs of the Tōkaidō was actually Kuniyoshi with 30 designs, followed by Hiroshige (21 designs), and Kunisada (eight designs)." This series of 59 ōban falls in a period when designers, actors, writers, and publishers had been imprisoned or expelled from Edo in the aftermath of the so-called Tenpō reforms (Tenpō no kaikaku). Only the joint effort of six different publishers made this series possible."

****

About the fan cartouches found at the top of each print in this series

Laura W. Allen wrote about these fan-shaped cartouches on page 9 in 'An Artistic Collaboration: Traveling the Tōkaidō with Kuniyoshi, Hiroshige, and Kunisada' in Tōkaidō Texts and Tales: Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui by Kuniyoshi, Hiroshige, and Kunisada: "At the outset someone decided that the publishers would promote their individual brands through the use of different-shaped cartouches... at the top of ht

Kojimaya Jūbei (小嶋屋重兵衛) (publisher)

Yūrei-zu (幽霊図 - ghosts demons monsters and spirits) (genre)