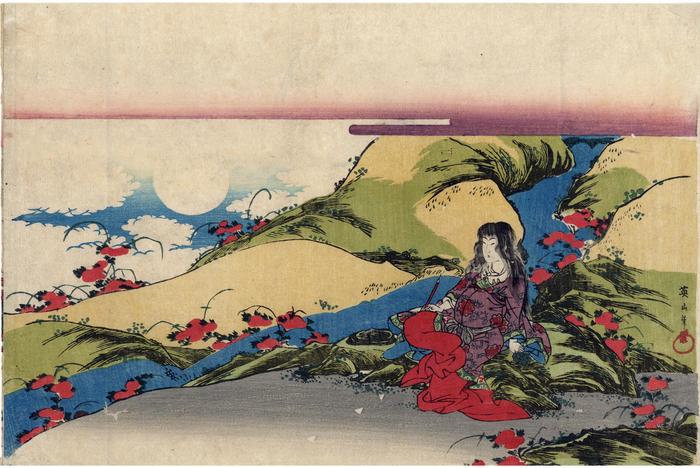

Kikugawa Eizan (菊川英山) (artist 1787 – 1867)

Scene from the noh play, The Chrysanthemum Boy (Kikujidō/Makurajidō - 菊慈童)

ca 1814

14.75 in x 9.75 in (Overall dimensions) Japanese color woodblock print

Signed: Eizan hitsu (英山筆)

Artist's seal: Kikudama [菊玉]

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive at the University of California There are nine prints from this series at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Six of those prints have a publisher's seal for Moriya Jihei plus the kiwame seal. However, neither the example here from the Lyon Collection nor the one in Boston bears either seal. Nevertheless, both prints were probably published by Moriya Jihei.

The subject of the other prints - not in any assigned order - in Boston are: 1) Crossing the Ōi River; 2) Firewood Gatherers Taking a Smoking Break; 3) Travelers at Futami-ga-ura; 4) Narihira's Journey to the East: Passing Mount Fuji; 5) Brine Carriers; 6) Cherry Blossom Viewing Party; 7) Travelers at Futami-ga-ura; 8) Travelers at Enoshima; and 9) Gathering Shellfish at Low Tide.

Notice that the Chrysanthemum Boy in this example has a brush in his right hand as he does in the example we have added by Shunshō. But unlike the Shunshō, this print shows Kikujidō holding a chrysanthemum leaf in his left hand, the leaf upon which he has written the inscription of the Lotus Sutra. Note that it is the moisture of the dew from the underside of this leaf which Kiku drinks and thus gains 800 years of immortality as a youth.

****

"Nine Chinese plays in the current repetoire feature a Chinese emperor as the central character. These plays can be divided into two groups according to their main themes. The first group consists of the plays Seiōbo, Tōbōsaku, Tsurukame, Kikujidō 菊慈童 (The chrysanthemum boy), and Hōso 彭祖 (Peng Zu), which feature Chinese deities offering blessings to the emperors as acknowledgment of their sovereignties.... Kikujidō and Hōso tell the story of essentially the same mythical character Kikujidō and involve the same motif of kikusui 菊水 (dew on chrysanthemums), an elixir for longevity."

Quoted from: China Reinterpreted: Staging the Other in Muromachi Noh Theater by Leo Shingchi Yip, p. 37.

****

The story of The Chrysanthemum Boy comes from a Noh play.

"In ancient China, an envoy is sent by the emperor to Mt. Rekken to find the source of miraculous water (fountain of youth) flowing forth from there. Deep in the mountains he finds Kikujidō in a hut, singing, "With the pillow of Kantan you dream of a hundred years of luxurious life, but every time I look at my pillow I am reminded of my misconduct which caused me to be here." (He had inadvertently stepped over the pillow of the emperor, who was therefore obliged to exile him to this remote mountain fastness). Kikujidō discovers that it has been seven centuries since he was exiled, and understands then that the emperor, in sympathy, wrote on the pillow two verses of Buddhist scripture, which Kikujidō has faithfully copied onto chrysanthemum leaves round about, and the dew from those leaves became an elixir of life protecting him from wild beasts, disease and death. Kikujidō dances and serves the elixir to the envoy, blessing the emperor and presenting him with his seven hundred years longevity."

Quoted from a reprint: A Spectator's Handbook of Noh by Mr. and Mrs. Murakami Upton, Tokyo, Wanya Shoten, June 24, 1968. Original date of publication unknown, but it must be sometime after 1960.

****

"In Japanese legends, the white and yellow leaves of the wild chrysanthemum confer blessings from Kiku-Jido, the chrysanthemum boy who dwells by the Fountain of Youth. These leaves are ceremonially dipped in sake to assure good health and long life."

Quoted from: The Nature of Shamanism and the Shamanic Story by Michael Berman, p. 132.

****

A homosexual subtext

David Waterhouse wrote in Impressions, vol 19, 1997, that Harunobu produced a mitate-e "...of Kikujidō, "Chrysanthemum Boy," a Chinese Immortal, whose real name was Zhang Zu. As a child he was a favorite of Mu Wang, the fifth Zhou [周] Emperor (ca. eleventh century B.C.); but one day stepped over the Emperor's pillow, on which were inscribed two verses from the Lotus Sutra. (It is not clear how the Lotus Sutra had come to be known in China at this date, since it had not yet been written, and was not properly translated in Chinese until the fourth century A.D.) For this offence, he was banished to the mountains of Li Xian, in the Nanyang district (of modern Henan Province), where he inscribed the two sacred verses on a chrysanthemum leaf and cast it into the water of a nearby stream. Afterwards, on drinking drops from the underside of the leaf, he discovered that he had attained eternal youth."

Later Waterhouse wrote: "From the seventeenth century onwards, however, Kikujidō and chrysanthemums were also associated with homosexuality, and there are senryū poems making fun of this. Harunobu's friend Hiraga Gennai, in his Nenashigusa (1763), remarks: "This word kikuza, 'chrysanthemum seat' [a slang term for the anus], derives from the love of Mu Wang of Zhou for Kikujidō."

Moriya Jihei (森屋治兵衛) (publisher)