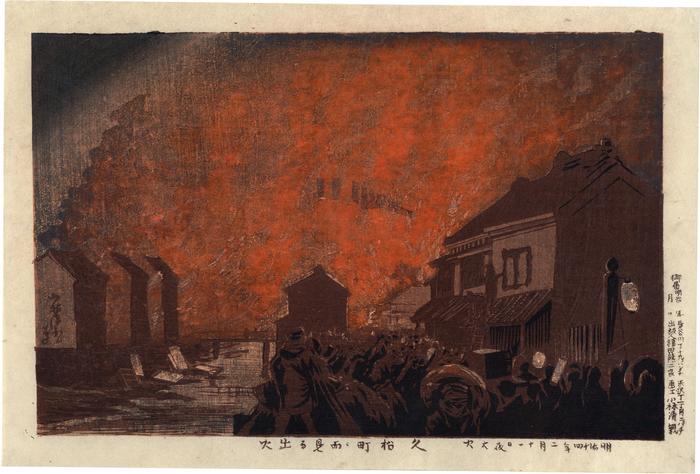

Kobayashi Kiyochika (小林清親) (artist 1847 – 1915)

Outbreak of Fire Viewed from Hisamatsu-cho (Hisamatsu-cho kara miru shukka - 久松町ニ而見る出火)

1881

Signed: Kiyochika hitsu (清親筆)

Publisher: Fukuda Kumajirō

Inscription - lower rt. margin:

"Great fire on night of February 11, 1881"

Meiji jūyonnen nigatsu juichinichi yoru taika (明治十四年二月十一日夜大火)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Edo-Tokyo Museum

Harvard Art Museums - in black and white, but with great contrast

Hagi Uragami Museum of Art

British Museum

Waseda University

Princeton University Art Museum

The National Museum of Asian Art - first of three versions

The National Museum of Asian Art - second of three versions

The National Museum of Asian Art - third of three versions

Adachi Museum of Art - first version without date or publisher's information - possibly a proof (?)

Adachi Museum of Art - second version

Keio University Library - first version

Mead Art Museum

Lyon Collection - another version

Carnegie Museum of Art

Carnegie Museum of Art - a second version

Rijksmuseum

Chazen Museum of Art

The Art Institute of Chicago

Keio University - 2nd version "The situation was different for another fire that broke out just fifteen days later, on the evening of February 11. Kiyochika's sketchbook shows that he made four single-page sketches of this fire (two in color and two in pencil), of which one... became the model for Outbreak of Fire Seen from Hisamatsu-chō... The popularity of this dramatic print is demonstrated by the large number of variant impressions in which it appeared, each with a different coloring to the sky."

Quoted from: Kiyochika: Artist of Meiji Japan by Henry D. Smith II, p. 50.

****

Illustrated:

1) in color in 原色浮世絵大百科事典 (Genshoku Ukiyoe Daihyakka Jiten), vol. 9, p. 93, #214.

2) in color in Ukiyo-e to Shin hanga: The Art of Japanese Woodblock Prints, Mallard Press, 1990, p. 191.

3) In a black and white reproduction in Catalogue of the Collection of Japanese Prints Part V - The Age of Yoshitoshi, Rijksprentkabinet/Rijksmuseum, 1990, no. 59, p. 50.

4) In two color reproductions in 小林清親: 文明開化の光と影をみつめて (Kobayashi Kiyochika: Studies in Light and Shadow of the Westernization of Japan, by Hideki Kikkawa, Seigensha Art Publishing, 2015, p. 79, #108 and 109.

5) in color in The New Wave: Twentieth-century Japanese prints from the Robert O. Muller Collection, Bamboo Publishing, Ltd. and Hotei Publishing, 1993, page 60, nos. 9a & 9b.

****

There is another copy of this print in the Adachi Ward Museum (足立 区立郷土博物館所蔵), Tokyo.

****

The flowers of Edo

"It is no wonder, then, that a fire was known as one of the "flowers of Edo" (Edo no hana), the flames and sparks lighting up the city sky like fireworks (or "flower-fires" — hanabi — as the Japanese more aptly put it). Edo's fires were likened also to momiji, coloring the city with hues as vivid as the fall show of maple leaves, only to leave behind a charred and desiccated wintry landscape. The doyen of post- World War II Edo studies, Nishiyama Matsunosuke, proposed a famous fourfold characterization of Edo as a "city of warriors, men, fire, and forced moves," the fourth chiefly a consequence of the third.

Fires were also called shukuyu and kairoku, names of ancient Chinese personages that were adapted as appellations for Japanese "fire gods." The Daikairoku, a nineteenth-century record of the three great fires of Edo, bespeaks that century's enshrinement of Edo fire folklore. The first of those famous fires — and the most momentous of all Edo blazes — was the great Meireki fire, in the first month of 1657. Also known as the Furisode fire, this was actually two successive conflagrations that destroyed most of Edo, including the castle and its keep, 160 daimyo estates, over 770 bannerman compounds, more than 350 temples and shrines, and nearly 50,000 merchant houses. The number of dead has been estimated at 108,000; the unclaimed were buried in mass graves at a site south of the Sumida River that became Muenji (later Ekōin), a favored site of sumo tournaments. Over a century later, the great Gyoninzaka fire of 1772 burned a path of destruction fifteen miles long and more than two miles wide. The trio was completed by the great Heiin fire of 1806, which started in the southern section of the city and cleared a swath six miles by one-half mile in six hours, claiming 1,200 lives and destroying 83 domain estates, 86 temples, and 530 residential quarters.

Most serious fires started in late winter and early spring, often sparked by cooking fires and heating braziers and then fueled by the seasonal north to northwest winds. Fully half of the recorded Edo blazes occurred in the final and first two months of the old calendar (roughly, the first quarter of the modern year). Often in this season, the wind fanned fires from the higher elevations of Hongō, Koishigawa, Ushigome, and Komagome down into the low-lying commoner wards between Edo Castle and the Sumida River."

Quoted from: Edo and Paris: Urban Life and the State in the Early Modern Era, entry by William W. Kelly, Cornell University Press, 1997, p. 311.

modern prints (shin hanga - 新版画) (genre)

landscape prints (fūkeiga 風景画) (genre)

Fukuda Kumajirō (福田熊次郎) (publisher)

Meiji era (明治時代: 1868-1912) (genre)