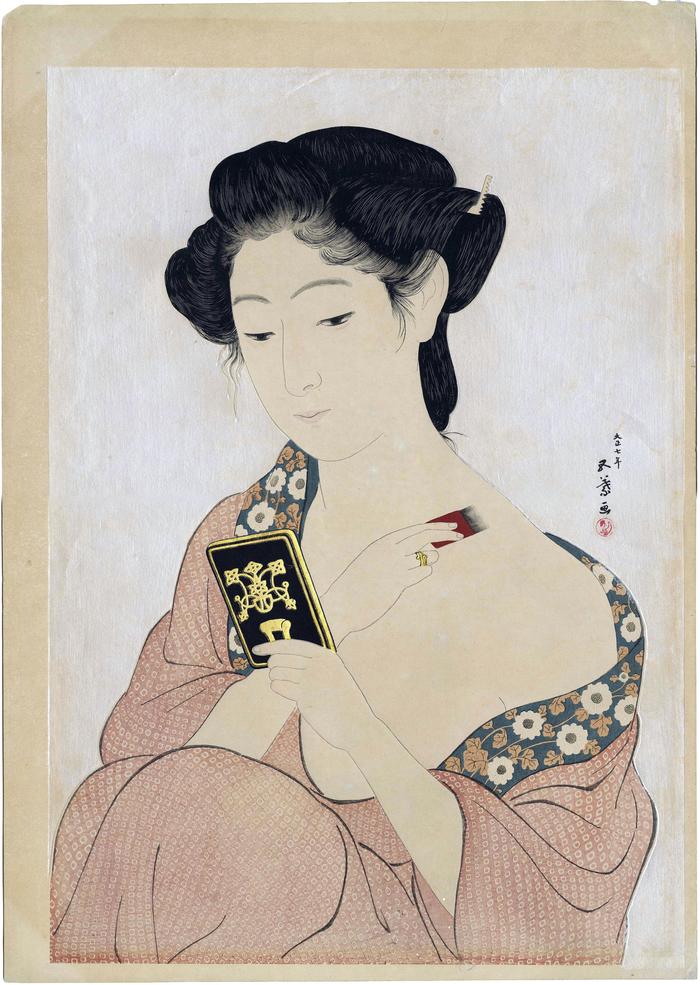

Hashiguchi Goyō (橋口五葉) (artist 1880 – 1921)

Woman applying powder (Keshō no onna) 化粧の女

1918

15.5 in x 22 in (Overall dimensions) Japanese woodblock print

Signature: Goyō ga 五葉画

Artist's seal: Goyō

Date: Taishō shichiren: 大正七午 (Taishō 7)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Nelson Art Gallery

Los County Museum of Art

The National Museum of Asian Art

Walters Art Museum

Rijsmuseum

British Museum

Harvard Museums

Art Institute of Chicago - the Clarence Buckingham Collection

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Honolulu Museum of Art

Dayton Art Institute

Nihon no hanga

Tokyo National Museum (via Cultural Heritage Online) Several sources, like the Art Institute of Chicago and the Minneapolis Museum of Art, note that the model is Nakatani Tsuru (中谷つる).

****

In The New Wave: Twentieth-century Japanese prints from the Robert O. Muller Collection it says on page 127:

“Goyō’s first independent print, Nude after the bath, was produced by Watanabe Shōzaburō in October 1915. However, the artist was apparently unsatisfied with the results, and he produced no more prints with Watanabe. In fact it was three years before he issued his next print. All his subsequent prints were published privately, perhaps due to his desire to participate in all aspects of the printing process. A woman applying powder, which depicts a young woman putting white powder on her shoulders, was Goyō’s second print. His debt to the masters of the Kansei era (1789-1801) such as Utamaro is clear, particularly in the use of rich mica backgrounds and the half-length sensuous close up depictions of women making their toilet. The use of gold highlights on the mirror and the woman’s ring, the blind printing for the chrysanthemum motifs on her kimono border and the bokashi on the kanoko kimono design, further add to the richness of the print. Such details are also evidence of Goyō’s high standards in the carving and printing of his prints: the block for this image was carved by Takano Shichinosuke (and Koike Masazō) and Maeda Kentarō assisted with the color blocks. Nevertheless, Goyō reveals his own training in a more realistic tradition in the creation of a subtle three-dimensionality, for example, in soft pink shading on the young woman’s skin.”

Collectors of Japanese prints in the late 18th and early 19th centuries must have recognized immediately the genius of Utamaro and his supernatural ability to transcend the ordinary when it came to portraying the beauty of the women that he knew. Those women are just as beautiful, sexy and evocative today as they were back then. The same can be said of this print by Goyō. A little more than 100 years old now, this woman is just as attractive as she was the day Goyō drew her. The pose, the bear shoulder, her hair, the slope of her neck are all as appealing now as they were then. This woman has, like Utamaro’s women, been immortalized for all time. We can only sigh and wish we had known her in person. This print is a poor second best, but, as you can see, better than nothing.

****

Lawrence Smith at the British Museum wrote of this print: "This is the grandest of the portraits of which Goyo personally supervised the printing. According to Blair (Blair, Dorothy, 'A Special Exhibition of Modern Japanese Prints', Toledo Museum of Art, 1930), the blocks and surviving print stocks of Goyo's small output were destroyed in the 1923 earthquake and are very rare. All of his female subjects are known to be geishas or waitresses in high-class restaurants or tea-houses, and hence professional beauties. In the 'Ukiyo-e' tradition of which he was a student he has concentrated the skills of the printer on the hair and the tie-dyed textile..."

****

There is another copy of this print in the Worcester Art Museum.

****

The printer is said to have been Somekawa Kanzō.

****

Illustrated:

1) in The Female Image: 20th century prints of Japanese beauties, Abe Publisher, 2000, #13, p. 40. (Referred to as 'Woman applying her make-up'.)

2) in a full page color reproduction in "Ten years of Nihon no hanga: An interview with Elise Wessels" by Marije Jansen in Andon 108, December, 2019, p. 36.

3) in color in Seven Masters: 20th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints from The Wells Collection, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2015, p. 55. Also in a small color image on p. 201.

4) in a full page color reproduction in Aziatische Kunst, 'Prenten' by Menno Fitski, vol. 37, issue 2, Brill, July 2007, no. 20, p. 30.

5) on the cover of Shin Hanga: Holzschnittkunst Japans in der ersten Hälfte unseres Jahrhunderts, text by Wolfmar Zacke, edited by Irene Zacke, published by Taschenbuch, 1993.

6) in color in 'Ten years of Nihon no hanga: An interview with Elise Wessels' in Andon 108, December, 2019, by Marije Jansen, p. 36, fig. 2.

7) in color in The New Wave: Twentieth-century Japanese prints from the Robert O. Muller Collection, Bamboo Publishing, Ltd. and Hotei Publishing, 1993, page 127, no. 128.

8) in a small color reproduction in Ukiyo-e: The Art of the Japanese Print by Frederick Harris, Tuttle Publishing, 2010, fig. 77.

9) in a full-page black and white reproduction in Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Early Years by Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1990, page 73.

10) in a full-page color reproduction on page 4 and again at page 87 in René Scholten's Personal Collection, Audap & Associés (an auction catalog), October 18, 2024, #126.

****

References: Hockley, ed., Women of Shin Hanga (2013), #20; Chiba Mus., Nihon no hanga II, 1911-1920 (1999), #253; Hizô ukiyo-e taikan: Mura (Muller coll.; 1990), pl. 107; Nihon hanga bijutsu zenshû 7 (1962), #36.

beautiful woman picture (bijin-ga - 美人画) (genre)

modern prints (shin hanga - 新版画) (genre)