Enjaku (猿雀) (artist )

Links

Biography:

Almost nothing is known about this Osaka artist. There have been several suggestions that he - and we are assuming it was a 'he' - as to who he might have been, but no one knows for sure. Was he an actor who used the name 'Enjaku'? Possibly, but probably not. What we do know is that there are a reasonable number of prints by him and many of them were originally printed in deluxe editions.

in 2006 a special edition of Andon was devoted to this artist. An article entitled: "Enjuka. An Osaka master of the deluxe print during the transition to the final period" by John Fiorillo and Hendrick Lühl goes a long way to unlocking numerous mysteries about this elusive artist. The information listed below is from that article.

On page 11: "Enjaku's surviving prints span a decade, from 3 /1856 to 4 /1866".

"Enjaku worked with at least twelve publishers: Daisei, Fugen, Honsei, Ishiwa, Kau, Kinkadō, Kinoyasu, Meikōdō, Tamaoki, Tenki, Uchitora, and Utayoshi... This diversity oÍ publishers for a relatively small body of work suggests that Enjaku was a sought-after artist, a conjecture further supported by the high proportion of deluxe issues of his designs... Had Enjaku been a less respected artist, he would not have been offered repeated opportunities to produce his work in these expensive editions, made with luxurious techniques and materials, including metallic pigments, embossing, burnishing, gradated shading, high-quality colorants, multiple hues of a single colorant, and unusual color combinations."

On page 14: " It appears that Enjaku's most active years were 1860-1861. Accompanying a significant spike in activity in 1861 was an increase in the number of publishers distributing designs by the artist. (The seals of Honsei/Tamaoka, Kinkadō, and Meikōdō have so far been found only on Enjaku prints from 1861.) There was a precipitous decline in 1862, although Enjaku continued designing prints until 1866."

"The most immediate influences on Enjaku... however, were the prints of the previously mentioned Osaka artists Hirosada and Kunimasu, as well as Hasegawa Sadanobu I (1809-1879)."

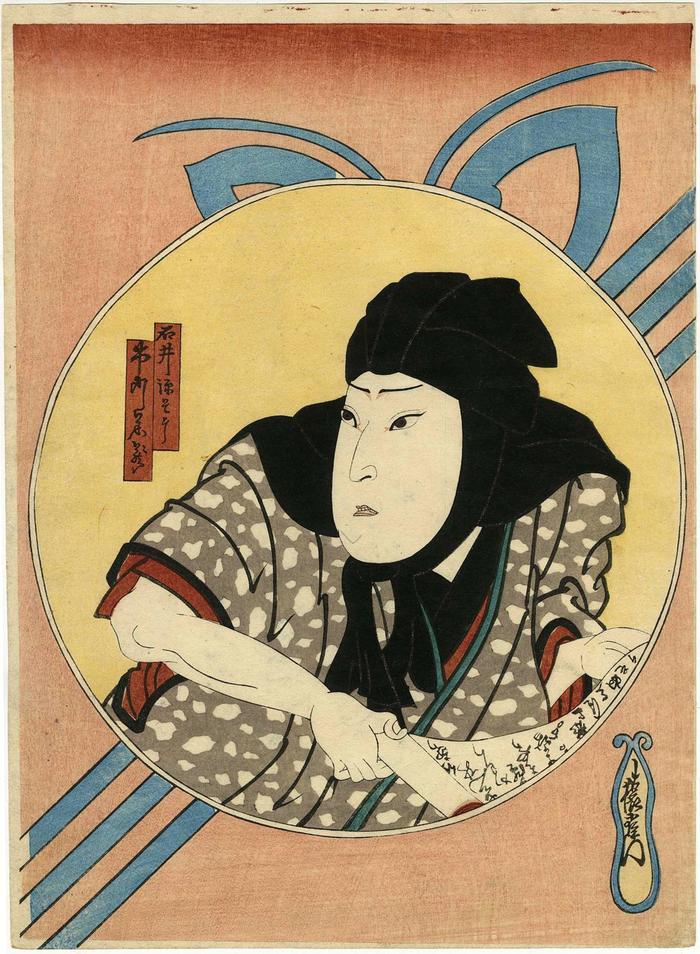

On page 15 is a discussion of Enjaku's portrait style: "Enjaku used a narrower range of facial types than did Hirosada, Kunimasu, or Sadanobu. A large majority of Enjaku's physiognomies were based on the oval or ellipse, falling short of the variety found in Hirosada's works."

On his use of colors on page 16: "Enjaku reflected a shift in the Osaka color palette toward hues that were generally 'brighter' than those used by Hirosada, Kunimasu, or Sadanobu. Such colors were an increasingly common part of the chromatic grammar of Osaka artists during the final period. Although Enjaku used vegetal and mineral pigments, their luminance and saturation were suggestive of a trend toward bolder colors..."

On page 16: "Enjaku's nigao-e ('Iikeness pictures') were clearly different from the preceding generation of artists, although accurate and consistent in their own manner. His portraits were notably refined when printed in deluxe editions. While all oÍ Enjaku's compositions were well conceived, the designs that truly catch the eye are those benefiting from the enhancement of special block-cutting and printing techniques. He was fortunate to have worked with some of the finest artisans of the period, and Enjaku's best deluxe-style prints are among the gems of the Osaka printmaker's art during the final period."

"... Enjaku's prints seems to indicate a singular achievement found in special commissions, notable but briefly realized. Later developments would overwhelm any such inclinations toward restraint or quiet elegance..."

Enjaku did collaborative works with Kunikazu, Yoshitaki and Hironobu. (p. 17)

On Enjaku's involvement with shrine theaters appears on page 18: "Enjaku was involved - to a surprising degree - with the shrine theaters at Inari and Tenma in Osaka. These two theaters accounted for more than half the performances depicted by Enjaku from among a total of thirteen different theaters. Such a focused connection with the shrine stages was most unusual among the accomplished ukiyo-e artists. Of Enjaku's 112 designs for which theaters have been identified, the Inari and Tenma shrines account for 28 (25%) and 35 (31%), respectively. If we combine all the known theater performances at the five shrines related to Enjaku's prints, they represent 64% (72 of 110). In contrast, three middle theaters account for only 12 (11%) and five large theaters a modest 28 (25%)."

Elsewhere, John Fiorillo said in his website 'Viewing Japanese Prints': "Enjaku (猿雀), active c. 1856-1866, was an Osaka print designer who is known today only by his artist's name (geimei). He produced more than 150 designs, with an extraordinary 88 percent in deluxe editions. Nearly all were chûban (about 10 x 7"), but five compositions were ôban..."

Fiorillo stressed the quality and rarity of Enjaku's prints. "Enjaku specialized in designing actor prints made with luxurious techniques (metallics, embossing, burnishing, expensive pigments, gradated shading, multiple hues of a single color). He worked with the finest Osaka block cutters and printers of the late Edo period. In some cases his portraits were significantly enhanced by the quality of the printing, and these works are among the most impressive examples of the printmaker's art at the start of the final period in Osaka. His prints were often issued without publisher's marks, possibly through private arrangements with block-cutter and printer workshops as special commissions from actors or their fan clubs and private patrons. Enjaku's deluxe designs must have been printed in small editions because many are known in only one or two impressions and very few show any signs of key block wear. Only later ordinary editions (i.e., without deluxe pigments or techniques) seem to show obvious thinning or breaking up of the key-block lines."