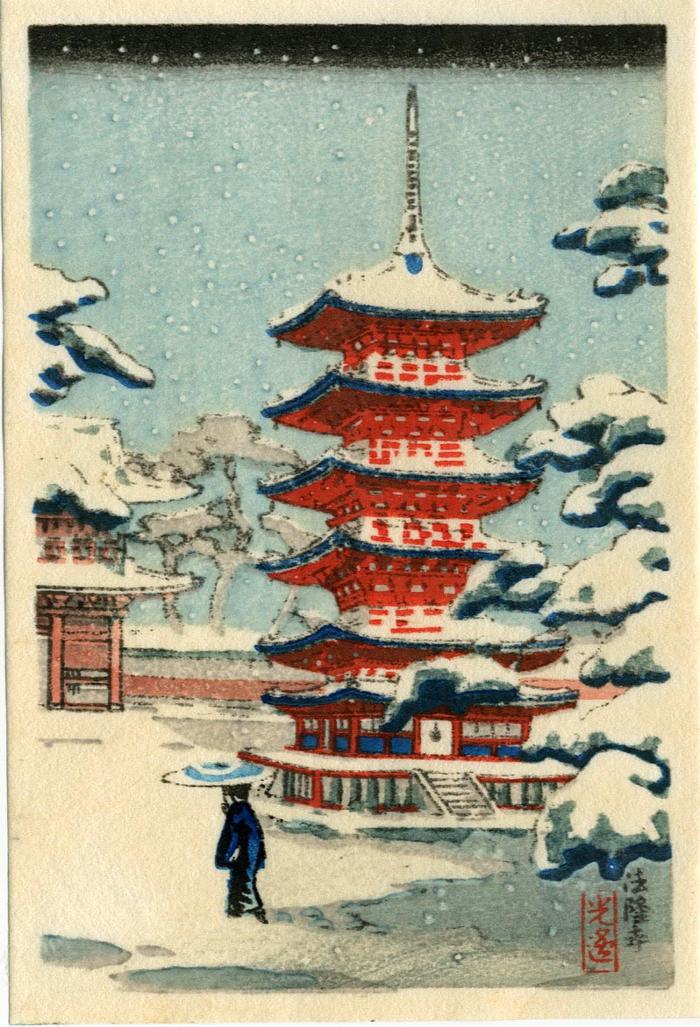

Tsuchiya Kōitsu (土屋光逸) (artist 08/28/1870 – 11/13/1949)

Tsuchiya Sahei (real name: 土屋佐平)Links

Philadelphia Museum of Art - one of Kōitsu's first woodblock prints - a Sino-Japanese triptych from 1895Ukiyo-e.org - an early lithograph by Kōitsu

Biography:

In a wonderful article, 'Tsuchiya Kōitsu (1870 - 1949). An artist's journey', from December 2010 in Andon the authors of the catalogue raisonné on Kōitsu, Ross F. Walker and Toshikazu Doi, wrote on page 27, ff.:

"Mention the name Tsuchiya Kōitsu and most collectors imagine a Shin hanga landscape artist who followed in the footsteps of the likes of Kawase Hasui and Yoshida Hiroshi. It will thus surprise many to hear that Kōitsu's artistic career lasted far longer than Hasui's, and that his oeuvre consisted of a wide variety of contemporary art forms, including woodblock prints, lithographs, scrolls, and watercolours. He lived an eventful life..."

He was born on August 28, 1870 in the Hamamatsu area of Shizuoka prefecture, but moved to Tokyo at the age of 15 "...and became a trainee at a temple, from where, upon the temple priest's recommendation, he transferred to Matsuzaki Shumei's engraving studio as an apprentice. This is where Kōitsu's destiny as a Shín hanga artist began: Matsuzaki Shumei was closely associated with the artist Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847 -1915), the so-called father of kosen-ga (Western-style light-and-shade technique), and it has been suggested that through this association Matsuzaki was able to urge Kiyochika to accept Kōitsu as one of his resident pupils. While studying as an apprentice under Kiyochika Tsuchiya Kōitsu started using the name Kōitsu as his artist's name [after 9 years of apprenticeship and therefore by 1895]." His first two independent works were triptychs that dealt with the negotiations ending the Sino-Japanese war. They were published by Takekawa and Inoue in 1895. He was also trained in lithography by Kiyochika and the authors said they had found 12 such prints with Kōits's signature dated from 1897-1904. Later he published more than 100 lithographs with Daihei (i.e., Daikokuya, also known as Matsuki Heikichi.)

Around 1904-05 he was diagnosed with pleurisy and gave up lithography. He spent some time at a sanatorium in Chigasaki. He had been married once before but his first wife had died. While on another stay in Chigasaki he met his second wife who died shortly after giving birth to a daughter. The infant was cared for by his deceased wife's sister and while Kōitsu moved back to Tokyo he visited Chigasaki often. In time he married the sister and the three of them moved to Tokyo. Then Kōitsu and his wife and daughter moved back to Chigasaki in 1922. A year later the great quake struck, devastated Tokyo and the entire art scene and Chigasaki suffered greatly, too.

Kōitsu had developed a working relationship with Shōbidō as early as 1904. But it wasn't until the 1920s, after the Great Quake, that he started to produce art works for Tanaka Ryōzō (also known as Shōbidō Tanaka) for the growing Chinese market. These were mainly painted scrolls. The woodcuts he is so well known for did not take off until the 1930s.

"While Kōitsu was busy painting hanging scrolls in Chigasaki, Watanabe Shōzaburō had been promoting the so-called Shin hanga movement. In November of 1931 Watanabe coordinated the Kobayashi Kiyochika Print Exhibition in Tokyo in commemoration of the seventeenth anniversary of the artist's death. This provided the opportune moment for Kōitsu to join the Shin hanga community for the first time..." In 1932 Kōitsu produced his first two landscape prints for Watanabe. Although they are undated on the print the scholarship appears to be solid for this attribution. Kōitsu's relationship with Watanabe lasted until 1940 during which time he produced 10 prints which were sold at or above comparable prices for those of Hasui.

While Kōitsu worked with many publishers he did his best work with Doi Sadaichi producing 77 prints. However, the majority of his prints were the tiny ones, like the one in the Lyon Collection. Sadaichi had started selling ukiyo-e prints in Japan in 1924 after his sojourn in San Francisco. "In December of 1931. Sadaichi published his first Shin hanga print - a landscape print by Kawase Hasui entitled "Winter Moon (Toyamagahara)' - and by June of 1932 he had issued a total of 12 Hasui prints. Although his relationship with Hasui only lasted for a short seven months, it was surely beneficial to his business, to the point where Sadaichi needed to find a substitute Shin hanga artist to make up for the loss of Hasui." Walker and Doi added: " Before long Tsuchiya Kóitsu and Doi Sadaichi met and agreed on mutual goals to offer domestic and overseas customers high quality woodblock prints. Their partnership lasted a good 10 years and was one of 'mutual necessity', in the sense that both Kóitsu and Sadaichi would have struggled to survive financially without it."

Of course, the market for hanging scrolls for sale to China eventually dried up due to the Japanese actions prior to the Second World War. Then the war with the United States had the same effect on his export of landscape woodblock prints. The whole war period was particularly hard on artists and Kōitsu was no exception.

Doi Sadaichi died on April 14, 1945 and Tanaka Ryōzō in 1946. After that and probably due to his advanced age Kōitsu only produced scroll paintings for his own pleasure.

Walker and Doi finished with: "As the last significant student of Kiyochika, Kóitsu was able to perÍect the kosen-ga techique: his prints portray light and shade in a way that is unmatched by any other Shin hanga artist."

****

In an article in Andon 91 from December, 2011, 'Publishers of Tsuchiya Kōitsu works', Walker and Doi wrote on page 30: "Takemura Hideo (also known as Takemura Shokai) was a small-scale publisher based at 45 3-chōme, Bentendōri, Yokohama. The most notable artist to work with Takemura was Tsuchiya Kōitsu; as was sometimes the case with artists who worked for multiple publishers simultaneously, Kóitsu used a different artist's name, Kiyoshi (清), exclusively for Takemura Hideo (see the appendix for examples of his seals). We were able to confirm without a doubt that the pseudonym Kiyoshi was indeed used by Tsuchiya Kōitsu when we found a Kiyoshi seal among Kóitsu's art materials donated to the Chigasaki Museum by his daughters."

****

"The landscape specialist Tsuchiya Kōitsu (1870-1949) produced dozens of "famous places" prints throughout the 1930s. Early in the decade, working for Watanabe Shōzaburõ, Kōitsu typically rendered places - Gion Shrine, Eight Views Ōmi - without patriotic associations. At the end of the decade, employed by the publisher Doi Sadaichi, Kōitsu turned increasingly to places - Miyajima, Kashihara Shrine - connected with military or imperial history, places that now had obvious commercial appeal. Typical of these works is his 1939 Nijūbashi representing, literally, the double bridge in front of the Tokyo Imperial Palace and, figuratively, the emperor as the essence of the nation... The utterly conventional composition, similar to the one found in school textbooks and the penultimate print in Tokuriki's Collected Prints of Sacred, Historic and Scenic Places , was appropriate for an iconic image. These prints, still inexpensive today, were probably published in large numbers."

Quoted from: "Out of the Dark Valley: Japanese Woodblock Prints and War, 1937-1945" by Kendall Brown, Impressions, No. 23 (2001), pp. 71-72.