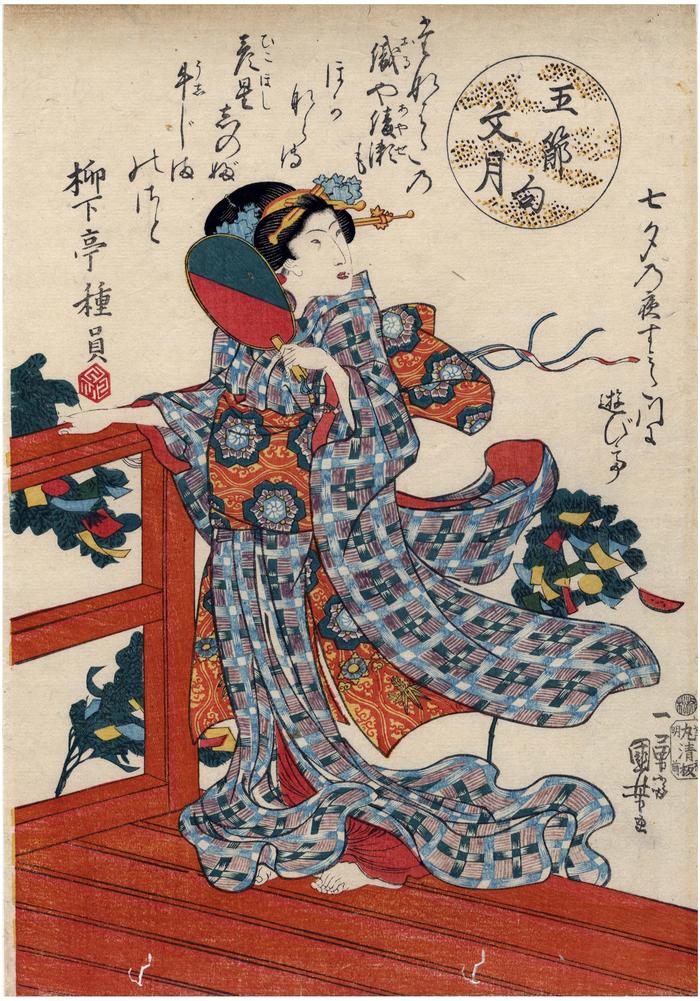

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川国芳) (artist 11/15/1797 – 03/05/1861)

A bijin on a small wooden platform during the Tanabata Festival (七夕) - from the series The Five Festivals (Go sekku - 五節句)

1843 – 1846

9.75 in x 14 in (Overall dimensions) Japanese color woodblock print

Signed: Ichiyūsai Kuniyoshi ga

一勇斎国芳画

Publisher: Maruya Seijirō (Marks 299 - seal 27-010)

Censor's seal: Muramatsu

Text by: Ryūkatei Tanekazu (柳下亭種員)

Kumon Museum of Children's Ukiyo-e - with explanatory notes

Lyon Collection - another copy of this print There is another Kuniyoshi print from ca. 1836 of this same theme and general layout. That one, however, shows a woman accompanied by a child. Whereas, we thought that this print in the Lyon Collection showed a woman on a bridge, it turns out, according to Iwakiri and Newland, in their catalogue Kuniyoshi: Japanese master of imagined worlds on page 92, that this is most likely a viewing platform.

They wrote of that print: "Mulberry leaf, brush and watermelon shapes decorated bamboo grass (seen in the background...). A woman and child stand on a rooftop look-out platform; judging by this woman's fluttering robes, it appears to be very windy."

****

Tanabata, the Weaver or Star Festival

Celebrated for ages as a lunisolar holiday held on the traditional 7th day of the 7th month. According to the Chinese tradition, adopted by the Japanese, the Cowherd (kengyū 牽牛), i.e., Altair in the Aquila constellation, the Eagle, travels across the Milky Way, to meet up with the Weaver Maiden (shokujo 織女, Vega in the Lyra constellation) for only one day a year. The name of the festival comes from Tanabata-hime (棚機姫} or Princess Tanabata who weaves fabrics for the gods.

"The legend of tanabata was already widespread at the time of the Man'yōshū -[compiled by poems composed from the 4th through the middle of the 8th century] - which account for more than 100 poems on this theme."

A progenitor of the Tanabata Festival was the kikōden or 乞巧奠 or the Festival to Pray for Skills. This, too, originated in China, but by the Heian period it had become a seasonal celebration adopted by the court nobility. Poetry competitions were common at this time. By the time of the Edo period this festival was included in the Go sekku - 五節句 and was extended to the population in general.

The Tanabata Festival came to be viewed as a prelude to the Bon (盆) Festival that honors the spirits of one's deceased ancestors. It also has a link to the origin of sūmo as a quasi-religious ceremony.

Source and quote from: Dictionnaire historique du Japon, 1993, page 48.

****

The quote above the bijin is by Ryūkatei Tanekazu (柳下亭種員: 1807-58). His name is shown along the left side with his seal. This author also wrote the text for Kuniyoshi's illustrations to the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety. (See #278.)

****

"Tanabata [七夕] originated in the ancient traditional belief that the Star Weaver which separated by Ama-no-gawa (Heavenly River) or Milky Way from her lover, the Altair, all the year round, meet once a year round meet once a year on the evening of July 7. Also it tells that Japanese women worshiped the Weaver as weaving was one of their most important household tasks in early days. Thus it is primarily a girls' festival. But since it became a national event in the seventh year of Tenpyo Shoho or 755, it has been most elaborately observed by all the people through 10 long centuries."

"The romantic belief that the Weaver and the Altair met only once a year appealed to the imagination or the sentiment of young girls. For the success of their own love they eagerly prayed at the festival. Also they prayed that the evening would be fair in weather, as they thought that, if it rained, the Milky Way would be flooded and the two stars would not be able to meet."

"In older days, all families planted long bamboos in their gardens and women and children tied onto bamboo branches tanzaku or oblong sheets of paper for poem writing."

Quoted from Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pages 105-106.

Note that beside the woman on our left are two bamboo stalks with written poem cards attached to them. There is one behind her too. During the Edo period elementary education was provided by teraokya (寺子屋) or temple elementary schools. Children would compose poems and tie them to the bamboo wishing for better calligraphy and sewing skills. The boys for calligraphy and math, the girls for sewing.

****

Go-sekku: the five festivals

In The Japanese Family Storehouse... by G.W. Sargent lists the five festivals as "...the seventh day of first moon, third of the third, fifth of the fifth, seventh of the seventh, and ninth of the ninth (Wakana no sekku, Momo no sekku, Ayame no sekku, Tanabata-matsuri, Kiku no sekku - though there are variants for most of these names)."

****

Claude Monet owned another print from this series. It now hangs on display at Giverny.

****

Brian Bocking wrote on page 147 in A Popular Dictionary of Shinto:

" 'Seventh night' usually translated as 'star festival' since it celebrates a legend from old China of the romance between a heavenly cowherd and a weaving girl. They neglected their work through love for each other and were punished by the god of the skies who ordered them to be set apart at each end of the ama-no-gawa, the celestial river or milky way. They were to work hard and could see each other only on the seventh day of the seventh month. On this day they could enter the celestial river because the god of the skies was away attending Buddhist sutra-chanting. The festival was officially recognised in 755 and was one of the five main festivals until the Meiji restoration. Tanabata involves the whole family and is widely celebrated in homes and schools regardless of religious affiliation. People connected with agriculture and weaving pray for help with these occupations, and youngsters enjoy making their own wishes on paper stars or star-spangled tanzaku (narrow paper strips for poetry). The major venue for the celebration of Tanabata is the city of Sendai in the north-east of Japan, where homes display decorations of tanzaku hung from bamboo poles and the streets are decorated with colourful paper streamers."

beautiful woman picture (bijin-ga - 美人画) (genre)

Maruya Seijirō (丸屋清次郎) (publisher)

Historical - Social - Ephemera (genre)

Ryūkatei Tanekazu (柳下亭種員 - 1807-58) (author)